NB: This article is part of the Bioenergetic Blueprint series. The series is meant to be read in order. You can find its table of right here.

If you’ve spent any amount of time in the bioenergetic space, you’ll have come across the claim that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), “because of their double bonds”, are weaker and more unstable than saturated fats. But how can this be true? Shouldn’t a double bond between atoms be twice as strong as a single one? Or, at the very least, stronger?

The surprising answer is: yes, double bonds are indeed stronger than single ones—but their marginally higher strength comes with two substantial drawbacks. Today’s article will help us appreciate this paradox.

By now we know electrons live in orbitals, and that the number of electrons neighboring an atom’s nucleus will influence the orbital’s shape. As more electrons join the party, they accommodate each other by arranging themselves in increasingly weird ways. Thus, s, p, d, f, etc. orbitals represent 3D wave functions that define regions of space electrons mostly inhabit when they have to coexist in a single atom.

But what happens when there is more than one atom at play? After all, atoms rarely exist in isolation. How do these orbitals adapt to allow atoms to bond with one another? And how do these bonds influence the way molecules behave?

To talk about all of this, we’re going to focus on carbon, the most important element in all of biochemistry, and how it forms covalent bonds with nearby atoms to achieve a more energetically-stable state.

Carbon, Meet Carbon

Let’s begin by remembering carbon’s electron configuration when it exists in isolation (which, again, never really happens across time, only briefly during reactions).

To recap: its 1s orbital is full, and so is its 2s orbital. But its 2p orbital is incomplete. Specifically, both the 2px and 2py orbitals are missing one electron to achieve a more stable state, and the 2pz orbital is missing entirely.

Now, we know that carbon likes to follow what’s known as the octet rule and “emulate” the behavior of noble gases by trying to achieve a full valence shell (consisting of 8 total electrons), since that is its most energetically favorable and stable state. After all, atoms with full valence shells are less likely to react with other atoms because they don't need to gain or lose electrons to achieve stability.

To do this, carbon is going to perform what’s called orbital hybridization: it’s going to combine its own electrons so it can form 4 bonds with other atoms.

Orbital Hybridization

We can visualize the electron configuration of carbon not using an orbital diagram, as we previously have, but one emphasizing electron energy levels, like this one:

As you can see, at the bottom is the 1s orbital, with its 2 electrons. Going up in energy we encounter the 2s orbital, with its 2 electrons as well. Going up once more we encounter the 2p orbital, with its 2 electrons distributed across the 2px and 2py orbitals. Thus, carbon is missing 4 electrons (depicted in light gray) for a full 2p orbital.

So, to reach a more stable electron configuration, carbon is going to combine its outermost orbitals (2s and 2p) to form a new 2spˣ orbital, in several ways.1 In doing so, it will get ready to form 4 bonds with other atoms and achieve a lower energy state. We can say this hybridization process occurs in two steps:

First, carbon promotes one of the electrons in the 2s orbital into the vacant 2pz orbital. This step, though energetically expensive, will pay off after all things settle.

Then, carbon “blends” its 2s and 2p electrons into a new hybridized orbital, in one of three ways:

Let me explain:

At the top, we have full hybridization. Here, carbon combines all of its 4 electrons from the 2s and 2p orbitals into a new orbital, called 2sp³ orbital.

The middle scenario represents partial hybridization. Here, carbon combines 3 electrons into a new orbital and leaves 1 electron in its old p orbital. The new orbital is called 2sp² orbital.

The bottom scenario also represents partial hybridization. Here, carbon combines just 2 electrons into a new orbital and leaves the other 2 in their old p orbital. The new orbital is called 2sp orbital.2

The question now is: what determines which of these scenarios carbon defaults to? And the answer is, of course, the type of bonds it will make with its neighboring atoms.

Strong Bonds, Weak Bonds

As depicted on the rightmost part of the previous diagram…

When carbon uses its new 2sp hybridized orbitals to make covalent bonds with other atoms, we call the resulting bond a sigma (σ) bond, where sigma represents the letter “s” for “single”. So, it results in a single bond. Pretty simple.

In contrast, when carbon uses its “old” 2p orbitals to make covalent bonds with other atoms, we call the resulting bond a pi (π) bond. The “pi” here is a reference to the p orbital. This type of bond can only happen in addition to sigma bonds, so in practice, it will always be the second bond in a double bond, or the second and third bond in a triple bond.

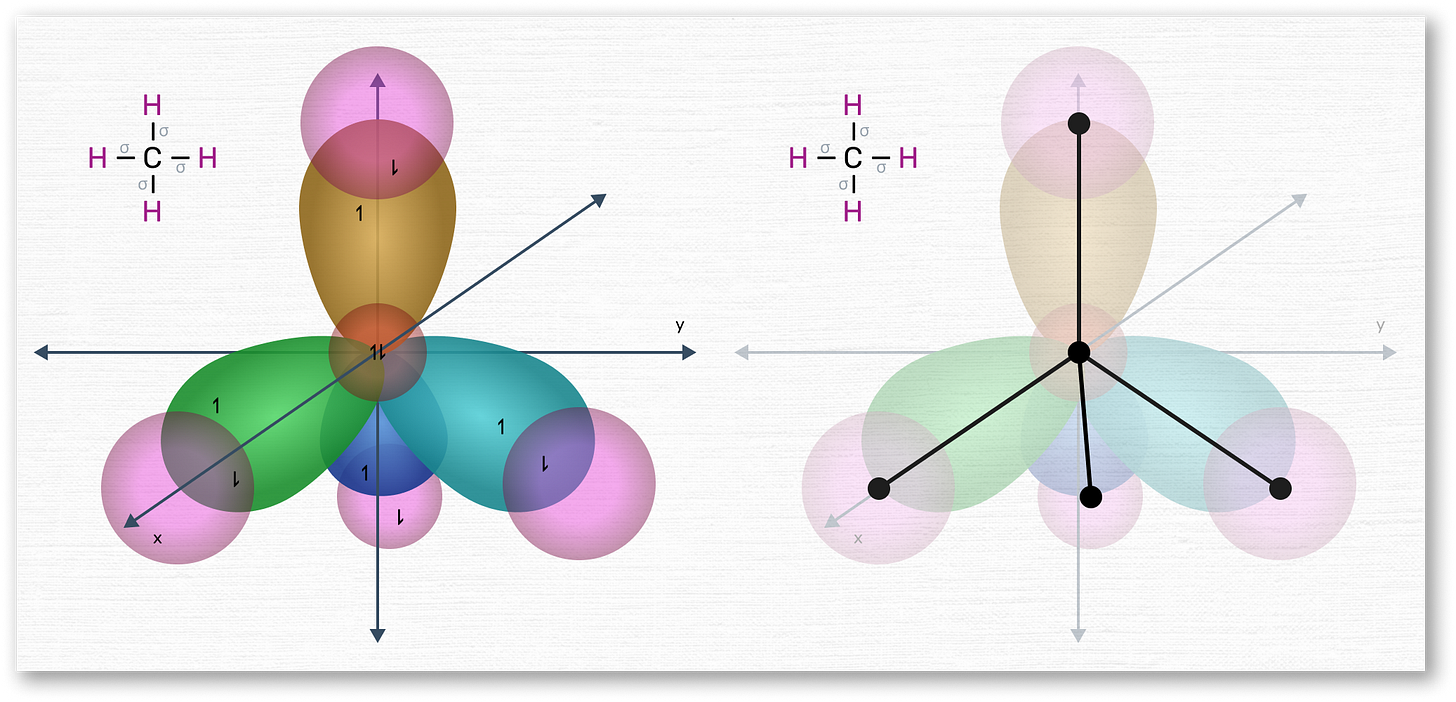

To visualize this a bit better, let us bring back our beloved orbital diagrams. Here is what carbon looks like when it hybridizes all of its valence electrons into four 2sp³ orbitals, as per the top scenario we described earlier:

As shown, the old 2s, 2px, 2py, and the temporary 2pz orbitals have hybridized to form four new 2sp³ orbitals, which are arranged like a tetrahedron. Unlike before, each orbital is now one single balloon (rather than being “double-ballooned”, like before).3

Carbon arranges its orbitals in this way when it forms 4 direct bonds with other atoms. For instance, here it is forming 4 sigma (i.e., single) bonds with 4 hydrogen atoms, in pink:

As you can see, the bonds happen directly, “face-to-face” with each orbital. As depicted on the diagram on the right, if you were to link the nucleus of carbon to any of the nuclei of hydrogen, you would do so with a straight line. Thus, sigma bonds are known to be strong and stable bonds.

But here’s the deal: When carbon cannot engage in four sigma bonds—for whatever reason—it will need to compensate by engaging in pi bonds because carbon “loves” to form four total bonds, one way or another.

Let’s look at ethene (C₂H₄) as an example.

Ethene has one double bond between carbons. This means it falls under the middle scenario (half-hybridization) where 3 electrons are combined into three 2sp² orbitals (ready to form 3 sigma bonds) and the remaining electron stays in the old p orbital (ready to form 1 pi bond).

If we were to look at a single molecule of carbon in ethene, it would look a bit like this:

As shown, along the vertical axis remains the good-old 2pz (double-balloon) orbital, and around it, three 2sp² squeeze themselves into place. The former is waiting to engage in 1 pi bond; the rest, in 3 sigma bonds.

So, what happens when another carbon like it approaches?

As shown on the left, the carbons form a sigma bond, which you can think of as a firm handshake (in green). This is the strong, “face-to-face” bond. This leaves both carbons with just 3 bonds in total (2 to hydrogen, 1 to each other), and no other low-energy way to engage in two more sigma bonds. So, as shown on the right, carbon will “improvise” another bond by having its (double-balloon) 2pz orbital electrons attract one another. We call this type of bond a pi bond.

As you can see, rather than a firm handshake, pi bonds look more like if two people tried to form the letter “O” together using their bodies: bending awkwardly towards each other to have their hands and feet touch. This bond—like all pi bonds—is not as strong as sigma ones, but it gets the job done.

We can actually measure the strength of these bonds in kJ/mol (i.e., energy per a specific number of molecules). A carbon-carbon single bond typically has a bond energy of about 347 kJ/mol; a double bond, of around 614 kJ/mol. This means the double bond has roughly 177% of the strength of the single one.

However, this increase in strength comes with a trade-off for the molecule as a whole. Yes, carbon-to-carbon double bonds are individually stronger, but they’re not twice as strong, so the molecule itself would be stronger—and thus more stable—if carbon engaged in sigma bonds instead. What double bonds gain in strength individually, they sacrifice at the level of the molecule.

The PUFA Case

Let’s apply this to PUFA. Below are three types of fatty acid molecules:

Saturated fat is called so because its entire carbon “spine” is saturated with hydrogens on both sides. So, carbon is engaging in sigma bonds all the way through.

On the other hand, unsaturated fats contain at least one carbon-to-carbon double bond. And whilst this individual double bond may be stronger than the rest, it “weakens” the molecule, since the latter would be stronger if each carbon engaged in a sigma bond instead. The double bond’s 177% strength comes at the expense of two additional single bonds for the molecule, each with 100% strength, so to speak.

But PUFA’s “weakness” it not only energetic: it is also structural. Single bonds allow free rotation of bonded atoms (a bit like magnetic beads do) which contribute to the molecule’s flexibility and adaptability. However, double bonds “lock” the involved carbons into place (since their 2pz orbitals need to be aligned), which prevents them from rotating freely, causing a more rigid and less adaptable molecule as a result. This also introduces the “kinks” that make the molecule’s spine angular.

Paradoxically, the flexibility of saturated fats is what makes their sources (e.g., coconut oil, butter, ghee) solid at room temperature. Their individual flexibility allows them to pack together closely and tightly. In this state, molecules get attracted to one another through Van der Waals forces (weak attraction due to temporary, uneven electron distributions), which makes them collectively sturdy. As a result, higher temperatures are needed to increase the kinetic energy of their atoms and make them “escape” the forces, separating the molecules and turning the fat from solid to liquid.

Conversely, the relative rigidity and angularity of PUFA make it harder for them to bundle up, which gives their common sources (e.g., sunflower oil, corn oil, fish oil) their characteristic liquid state even at cold temperatures. In fact, that’s exactly the reason why the fat from cold-water fish is necessarily unsaturated: if it wasn’t, the fish would be rigid as a cold stick of butter—and sink like one, too.

Conclusion

So, we now know, more or less, how atoms form bonds with one another, and what these mean for their structural and energetic stability. In the next article, we’ll take a closer look at why these interactions happen in the first place, by discussing the all-important concept of redox reactions.

Upwards!

Yago

Want more articles like this one?

Leave a comment, a heartfelt “like”, and share it with your loved ones!

Premium Courses

Modern Detox: Cleanse yourself from the modern world

Nurturing Nature: Cultivate yourself with timeless habits

Free Resources

Impero Wiki: The resource hub for aspiring Renaissance Men

While it could theoretically fill up the 2p orbitals instead, hybridization allows carbon to form four equivalent 2sp³ orbitals, each capable of forming a strong, stable covalent bond, leading to a more energetically favorable and stable state.

If the names confuse you: The digit refers to the energy level (still 2 in all cases). The letters refer to how many 2s and 2p electrons the new orbitals include. So, for instance, 2sp³ means energy level of 2, then one 2s electron and three 2p electrons. Think of it as a 2sppp orbital.

Actually, this is not entirely true. They are still “double-ballooned”, but the other balloon is in fact tiny and insignificant, so I’ve removed it from the diagram, for visual clarity.

Amazing understanding of the big picture and details of biochem. Wish this series was available when I was in my first year of Uni. can't wait for what's to come next!

Yago -- did you ever wrote the "next episode" -- Redox Reactions" ??

I definitely can't find it on your site. Please help if you did -- many thanks in advance